"My Students Are Forgetting What Writing Is."

Recently, I was talking to a professor about Generative AI. At one point in the conversation, he paused and sighed.

My ears perked up. I felt like something interesting was about to happen.

He said this, sounding somehow both matter of fact and solemn at the same time: “My students are beginning to forget what writing is.”

Here’s what he meant.

The Paradox of Modern Creation

A student of theirs recently handed in an assignment.

When the professor saw it, they correctly identified it as fully AI-generated. They approached the student, to see what happened.

The student was very honest. They had used ChatGPT. They prompted the AI program. They gave it feedback. They asked it to keep changing the output until they were satisfied. Then, they handed it in.

The student proclaimed, “I wrote it.”

They weren’t being facetious. They weren’t beating around the bush. The were claiming that they wrote the final product, even though they had not written a single word included in that final product.

It’s a startling idea. For the student, instigating and prodding amounted to full ownership.

I wrote about is on LinkedIn, and I soon realized that my student’s approach was far from isolated.

This is what that student was talking about. If the student hadn’t gone into ChatGPT and hadn’t written that prompt, then the output wouldn’t exist in the world. Being an author doesn’t mean having a hand in the final output: it means doing something that causes a written product to exist in the world. It also means being accountable for that product, for better or worse.

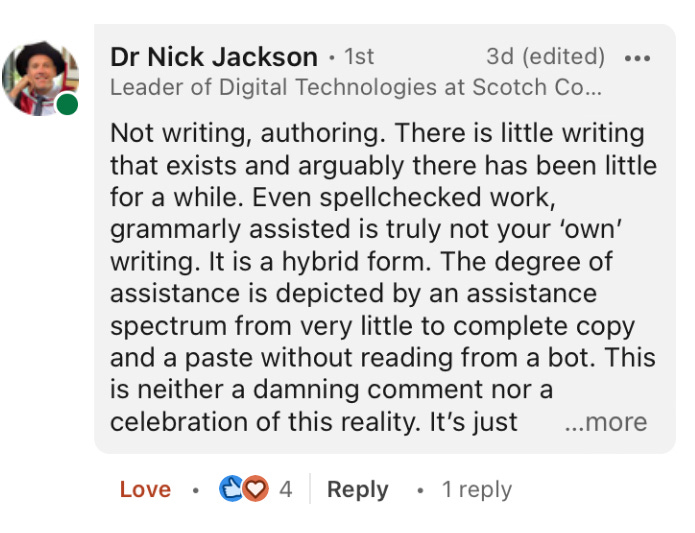

But let’s talk about that word: “authoring.” A friend of mine, Nick Jackson also homed in on the same term:

I get the point. It also shakes me to my very core.

“There is little written that exists and arguably there has been little for a while.” The traditional core of writing—where I put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard and directly create a publishable output—has been changing for a long time.

Grammarly and Microsoft Word’s spellcheck weren’t just helping me. They were gradually distancing me from the written product, even if little by little. The result is a hybrid form.

The Rise of “Writing from a Distance”

Nick Jackson’s idea gives me a middle ground for describing what this student had done.

The student is writing from a distance, meaning that he has a hand in generating the output even if he doesn’t have a direct hand in that output. Perhaps that’s representative of what is happening with society more broadly. Soon—so we’re told—we’ll be able to carry out many actions through AI agents and other technology. I’ll be able to use HeyGen to send thousands of clones into my Zoom meetings instead of attending them myself. I’ll have agents that can speak for me. I’ll delegate more, do less.

But wait…I’m not willing to give up on my definition of writing yet.

I understand that I’ve become accustomed to computer programs standing between myself and my writing, as a helpful intermediary. Even as I type right now, Substack underlines my words each time I mistype or miss a letter.

I give up a teensy bit of ownership over the output in return for a computer program’s help.

But there’s a difference between typing out the letters, words, and paragraphs in sequential order and what this student does. Writing them out does something to my mind.

Writing is exciting to me for two reasons.

It forces me to engage with the little details of language.

I may have Big Picture ideas on my mind, but I will need to wade through the minutiae of language to get there. And as I wade through that minutiae, I will inevitably encounter new ideas that spring from my own brain.

It creates something that feels like it’s mine.

Now, we’re going to head into the straight-up subjective.

The student will likely say that his model of writing satisfies these requirements. He wrote the initial prompt, and iterated. He wrote sequential words and sentences, and engaged with the details of language. And he certainly felt ownership over the product.

But he’s comfortable with much more distance between himself and his writing than I am. I’m not saying that a judgment. I’m saying that as an observation.

So, I don’t know.

I do know that, to this day, I find this model of writing as interesting as I find it unsettling.

For the moment, that’ll have to do.

I end with noting that I think traditional writing is valuable, and remain so. I am worried about what happens when—in the spirit of modern “authoring”— we become increasingly comfortable with a wide gap between the author and what they authored.

I worry about this means for writing as method of personal discovery.

I worry about what this means for modern accountability.

Perhaps I’m just a worry wart. Perhaps I’m not worried nearly.

It’s hard to tell these days.

Read this right after reading a semi-viral LinkedIn post about how if you (the ephemeral you) are not using AI to do all your writing, you’re failing. Your article regenerated a bit of hope that had otherwise been aggressively drained from my body when I read that LI post.

Writing is about so much more than producing words; it’s critically thinking, researching, organizing thoughts, struggling, failing, trying again, editing, refining, etc. All skills that echo into our lives in a myriad of ways. We need to know how to write not so we can get leads or create useless filler content but so we can understand information and communicate clearly for ourselves and our communities.

Sorry, I’ll give you your soapbox back 🫴

I read a piece recently in a book called "Learning from Cheating" that suggested students are so used to sampling, forwarding, re-posting, re-using digital content that intertextuality IS their language. So they don't even think a) it's cheating or b) it's meaningless. Their endorsement counts as, let's say, "publishing." And that DOES mean they're not creating from the blank page. So I'm looking for the new launch-pad that compares to the blank page. I think that's where we're headed...a variety of launch-pads.